Today was the last hard day of the trip. We left early at 8 am for the drive to

Birkenau, because the camp is enormous and I needed at least three hours in

it. I warned the students that Birkenau

was far larger than Auschwitz, but you could put Auschwitz I in a small corner

of Birkenau and you might not even notice it.

Auschwitz I held about 11,000 prisoners; Birkenau (Auschwitz II) held

about 100,000 slave laborers at any given time. It was the largest slave labor

camp in Europe.

After walking through the main gate, we went

to the ramp and I had the students read an excerpt from Yaffa Eliach’s book Hasidic

Tales of the Holocaust. This was a

story told by Jack Garfein about how at age 13, he and his mother arrived in

Birkenau and stood on the ramp awaiting the selection. His mother shoved him away from her into the

men’s column. The man behind him lies to Dr. Mengele, telling him that Jack was

16 and an apprentice mosaic artist. When

Mengele sends both of them to life, Jack, not understanding what just happens,

turns around to apologize for the lies, but is kicked by a kapo.

He soon learned how the man behind him, who

he described as a gentle Talmud scholar, had saved his life. For weeks, he searched for the man to thank

him, but one day he realizes that he’ll never find as he was the Prophet

Elijah, sent by his mother’s prayers to save her only child.

From there we walked the path of those

selected for death; it takes about 5-10 minutes to walk from the ramp to gas

chamber and Crematorium II. Historians estimate that around 500,000 people

were murdered in this one gas chamber.

With Soviet forces approaching, the SS evacuated some 60,000 prisoners

on January 17 and 18, 1945. Prisoners

were forced to march in heavy snow and bitterly cold temperatures (all while

wearing only pajamas and wooden clogs) between 30 and 35 miles to the nearest

rail station. About a quarter of the

prisoners collapsed or were murdered on these death marches. On the 20th, they blew up the

crematoria in an effort to conceal what happened in the camp. Soviet forces

liberated the remaining 7,000 prisoners scattered among the camps on January 27th.

After walking all around the physical space,

we sat nearby in the shade and read excerpts of Filip Müller’s interview in

Claude Lanzmann’s film Shoah. Müller

was Czechoslovakian Jew who was forced to become a Sonderkommando [a

prisoner who carried bodies from the gas chamber] in 1942. He was one of only a handful of Sonderkommando

to survive, as he managed to live through five liquidations, including the

revolt of the Sonderkommando that took place in Crematorium IV on 7

October 1944. In the chaos of the

evacuation of the camp, the SS forgot to shoot the Sonderkommando, and Müller

was death marched to Mauthausen. A week

or two after they arrived there, the SS asked all Sonderkommando from

Auschwitz-Birkenau to step forward and identify themselves (in order to kill

them). None did. He was liberated by American forces on 5 May

1945.

Müller describes in graphic detail how the

killing operation worked. While I think

everyone understands that being murdered in a gas chamber was bad, other than

historians, very few people realize how horrible and painful it was. As soon as the victims were inside, the doors

were sealed, the lights turned off, and the particles of Zyklon B dropped in

from the ceiling. Zyklon B was a solid,

gravel-like compound which then sublimated into a gas in the warm, damp gas

chambers. As the gas began to rise from

the ground up (it was heavier than air), terrible panic would break out in the

gas chamber as people fought in the pitch-black darkness. Since so many attempted to break through the

door (which was impossible), their bodies were piled up against it, and would

fall out in an avalanche when the Sonderkommando opened it 30 minutes

later.

Our second reading from Müller involved the

murder of the first Czech family transport in March 1944. The Sonderkommando warned the

transport that they were about to be gassed and offered to rise up in revolt

with them. The issue here was that this

transport was in relatively good physical shape (only 25% had died after six

months) and couldn’t be tricked into the gas chambers. In fact, though, the violence used against

the Czechs was extraordinary and physical revolt was simply impossible. The most they could do was to refuse the

order to undress. Instead, they sang the

Czech national anthem and Hatikvah.

Müller, watching all this in the undressing

room, decided to commit suicide by walking into the gas chamber with them,

which he did. Standing there, a group of women approached him and urged to

leave and bear witness to their suffering. Although he didn’t say it in the

interview, in his autobiography, Müller says one of the women shoved him into

an SS guard, who recognized Müller has a Sonderkommando and then threw

him out of the gas chamber screaming “we decide when you die!”

I have the students read all these excerpts

because, well first, because I need to save my voice, and second, because I

start to break down and cry if I read them myself. The students’ faces were ashen and shell

shocked as we walked to the so-called Sauna, where prisoners selected

for slave labor were inducted into the camp.

After walking through the undressing room,

the hair cutting room, the showers (which were either boiling or freezing), and

the room where they received their prisoner uniforms, there is a photography

exhibition of family photos of Jews from one Polish town (Bȩdzin). Looking at the various pictures, some

students found images of children that matched their nieces and nephews.

It’s a rather long walk back to the front of

the camp to the quarantine barracks. The

area around the gas chambers is wooded and swampy. The woods existed back then as a sort of camouflage,

and the ponds were where some of the ashes of those murdered were dumped. We went into some of the open wooden barracks

to see the conditions of the prisoners.

By now we had been in Birkenau for over two

and a half hours. Our last stop was the

women’s barracks, Camp Bia. This is the

earliest part of Birkenau, and many of these barracks were built from brick and

concrete. The later parts of the camp,

BII(a-e), were built from wood, and all that remains of almost all of them is

the brick heating channel in each barrack (if prisoners could find or steal

some wood, they could burn it in winter to warm the barracks).

Most of the barracks are closed for

restoration or preservation. We entered

a few. Block 16a, where 600 Polish

children deported to Birkenau from Warsaw or Zamosc, were kept here. Some of the prisoners had painted images for

the children on the walls of the barracks, so these horrible, dark places were

slightly less terrible.

Most of the other barracks contained up to

1000 Jewish or Roma women, forced to sleep 6 to a single bunk of a three-tiered

bunk bed (18 per bed). I told them how

Kitty Felix, brought to Birkenau with her mother when she was only 16, survived

the camp, and how her mother was able to survive as well, working on the

hospital block.

After spending over three hours in the camp,

we headed across the street to the parking lot, where I bought the students

lunch at the bus stop café (café is too generous a term for it). We rested for about an hour, and then we

headed to our last stop of the day, the Labyrinth art installation by Marian

Kołodziej at the Franciscan monastery in Harmȩze.

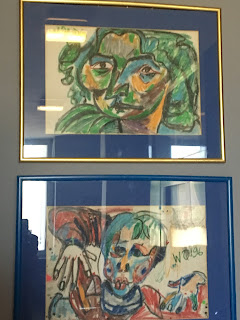

This is the third time I’ve taken students here

and we had Renata, the same wonderful guide we had two years ago. Kołodziej’s

art powerfully conveys the horrors of the camp and addresses the experiences of

prisoners (he was on the first transport to Auschwitz in 1940) through

religious imagery. Through his art, he

calls on us not only to witness his and the other prisoners’ suffering, but to

make better choices in our lives.

I knew better than to try to talk about this on

the long drive back on the bus. It’s

just not conducive to having a discussion.

Because of road construction, the last two days we were forced to take a

detour through a small town. I noticed

the first day a large mural labeled “White Power” on the wall of a garage, and

the students had seen a sign saying “Anty-Jew” with a Jewish Star in a circle

with a line through it. I had my camera

ready and I managed to photograph some of it, but not all.

Back

in Krakow, we gathered in the breakfast room and talked about the day for about

45 minutes. Students were reluctant to

speak, but that’s not unusual. Most said

a few words, but there was also plenty of silence. I think it’s important to give them an

opportunity to think about and process what we’ve seen.

That

really ended the substantive part of the class.

Today is our last full day in Poland and it will be very light: some synagogues in Kazimierz this morning,

Wawel Castle at 12:30, and a farewell dinner tonight.

I

took all the students who wanted out to dinner last night at a somewhat kitschy

Polish restaurant in the Stare Miasto. I

had the top sirloin, but it was cooked medium to medium well, and I wasn’t all

that happy with it. Another student had ordered it and hers was medium rare.

Since she preferred medium well, we switched about two thirds of the way

through and both of us were happy.

Six

of the students ran out to join a pub crawl and the rest of us went looking for

a place for dessert.

There

was a big festival in Krakow yesterday; something to do with the summer

solstice. We saw a lot of women with

flowers in their hair so I asked a woman of a certain age waiting at the tram

stop with us if she spoke English. She

was from Belgium. I asked if she knew

why the women had flowers and she said that it was just a Polish custom. I knew that wasn’t right, but I wasn’t going

to argue with her about it. We talked

about Belgium for a little bit. She and

her friend were from Ostend. I told her

my favorite chocolate was Neuhaus, but she preferred Côte d'Or.

I asked what she was doing in Krakow and her

voiced dropped to nearly a whisper as she told me that her father had been in

the Belgian resistance during the war, and that he and his friends had been

sent to Auschwitz. They had been at the

camp earlier that day. She then added in a whisper that ISIS was becoming just

as bad as the Nazis.

When we got of the tram I could see a stage set

up on a small side street, and there was a concert, so I grabbed the students

and walked over to see what it was. This

street houses the French, American, and German consulates, and they sponsored a

street fair for the holiday. Here I

finally learned why so many of the women were wearing flower wreaths. In the old days, a maiden would toss her

wreath into the river and whichever boy recovered it would win a date with

her. At the German booth, they were

giving away CDs of music composed in Leipzig (mostly Bach) so I picked one up.

On the stage of main rynek there was a huge crowd

watching a Polish woman sing hard rock songs.

On the way back after dinner, the crowd was even louder, listening to

Polish rap. Like salmons swimming upstream,

we made our way through the throngs heading to the main square and found a

place for tiramisu and ice cream.

When we left, we discovered the concert had

ended and seemingly everyone was now walking our way. After we got back to the hotel we found out

why. I was just starting to type up this

post when I heard loud explosions. My

first thought was terrorism, but when I saw the reflections of light on the

building opposite, I went to the window near the elevator facing the river and

saw a massive fireworks display based around the river and Wawel Castle. The

explosions were remarkably loud and seemed to shake the building. As I was only on the second floor above

ground, I couldn’t see the lowest explosions, but what I could see was pretty

spectacular.

It lasted a good 15-20

minutes. It was a nice way to end the

day.